Description

You can download your FREE report on how you can avoid financial mistakes as a dentist using the link just here >>> dentistswhoinvest.com/podcastreport

———————————————————————

Have you ever felt the itch to reinvent your life, to take your expertise and passion and channel them into something entirely new? That's exactly what Dr. Michael Alasaras did when he traded his dental drill for the drawing board, embarking on a journey from oral health to inventive genius. This episode is a riveting narrative of metamorphosis, where a dentist becomes a beacon for innovation, challenging the status quo and transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary.

Our conversation with Michael is not just about a toothbrush; it's about the audacity to reimagine and the dedication to see that vision become reality. He shares how a simple act of curiosity, like taking apart toys in his youth, sparked a cascade of creativity that later allowed him to revolutionize dental products. As you listen, you'll discover the surprising synergy between dentistry and design engineering and why a mindset focused on learning and exploration can lead to game-changing innovation. Michael's insights will inspire both aspiring creators and seasoned professionals to look at everyday objects with fresh eyes.

Tune in as Michael opens up about the nitty-gritty of turning an idea into a thriving business. From crafting a robust patent application to mastering the art of material selection, this episode is a masterclass in entrepreneurship. You'll learn why early market feedback is crucial, the steps to achieving product-market fit, and how to navigate the complexities of branding and trademarking. Join us for an episode that's as much about the joy of creation as it is about constructing a company from the ground up, with a revolutionary dental product that's set to change the face of oral health.

Transcription

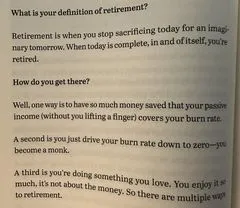

Dr. James, 2s:

Welcome to the Dentists Who Invest the podcast, everybody. Another interesting episode today will continue in the hot streak of late or super interesting episodes, and the reason I say this is because I've a dentist sat in front of me, dr Michael. Dr Michael Alasaras, I said your last name right, didn't I?

Dr. Michael, 19s:

Did. I knew it. Yeah, I got it.

Dr. James, 21s:

I'm notorious for mispronouncing Michael's last name, unfortunately even though Michael. I've known each other for three years now. Michael was super interested in his story because he was a dentist and he was halfway to becoming an airline pilot. Halfway to becoming a property investor. Covid changed his plans, changed his perspective on life and perspective on where he was going to go next and now we've got a super interesting product that you've created. You went through all the trials and tribulations of product designers you're going to hear about in this podcast and shine a light on that world to illuminate the path for other dentists who may have this passion and desire with some sort of concept that they dreamt up of. We're going to get into that in just a minute, but just before we do, michael, how are you today?

Dr. Michael, 1m 3s:

Very well, James. Thanks for having me on. It's an honour.

Dr. James, 1m 5s:

Hey bro, it's my freaking pleasure.

Dr. Michael, 1m 7s:

It's been a long time coming and I really want to try this story because it is a cool one.

Dr. James, 1m 11s:

You know, and actually a big part or a big point of Dennis Union Fest is to put cool alternative stories on the platform, to show other dentists out there and not just dentists, just anybody, really people what's possible in this world. Because a lot of this stuff that we speak about in the podcast and a lot of stuff in your journey well, I can relate to it, having left Dennis Union myself and having understood that there is other realities out there and we can inspire everybody who has that desire to understand that that is possible. If we can inspire them to realise that that is possible. And that's definitely going to be a cool thing, depending on what their goals are. Obviously, if they're happy in dentistry, that's fine. If they want to take a step out, well, speaking of someone like yourself, as I say, is going to illuminate that path for them. But anyway, before I bang on too much, michael, it would be really interesting to hear it directly from you, directly from the source. A little bit about you.

Dr. Michael, 2m 7s:

Yeah. So I qualified from Glasgow 20 years ago and basically I had the vision to go straight into private practice as soon as possible. I could see as an undergraduate the amazing skills that were being given and the standards that were being encouraged just wouldn't fit in the NHS dentistry business model, if you like, and so that's kind of what I pursued. But I did have a few SHO jobs, which were incredible, to be paid and be trained at the same time as such a gift, and then basically called every practice in Edinburgh asking for an associate job private practices only and two practices interviewed me. I got into one, which was the first step in stone, really, and through that practice I was introduced to another private practice owner and became his associate as well. But then within six weeks he said Michael, I want you to take over the practice. I was like, right, well, okay, I'm only 26 but I really do want this. It's just a bit earlier than I expected, so let's get on with it. It was an amazing team, a nice small two surgery practice, long established private. So I just got on with it and I was there for 11 years. On paper and clinically it was just tremendous success, but I was miserable. It's just the nature of being pulled in all directions, especially within a small practice. I'm kind of doing everything so I could have delegated better perhaps, but essentially I think you know, realised this wasn't going to be for me in the long term. But I stuck at it for 11 years and, you know, learned as much as I could from every challenge and there were constant challenges then. It's just dynamic and you know, the career changes almost every year. So, yeah, I started looking at an exit and along that path I had been coming up with lots of product ideas. I think by that point there were like 50 or 60 on the drawing board and I just kept redesigning everything around me and questioning the status quo and product design, engineering of everything tools, instruments, toys, automotive parts, whatever was in front of me. I just had this kind of inquisitive nature and design, product design and function. So this was kind of a burning passion that was lingering inside me and I realised actually I could get on with one of these ideas, at least when I saw patients with a particular dental problem which I can come back to later. And there I go, prox tooth brush solves. So along comes the practice exit. But I also had this other burning passion which I hadn't mentioned, which was to become an alien pilot since I was like 10 and as a schoolboy I ruled out completely because of the vast expense and training up to that level and that you essentially needed sponsorship and also that I had severe myopia. So that would kind of basically ruled out. But as I was exiting the practice I realised there was this affordable, modular pathway to become an alien pilot. So I thought, okay, I could become an alien pilot, product developer, maybe get into some investments and start a family, so that should keep me busy enough after selling the practice. So that's all the practice. I started on all of the above and, yeah, the airline industry was decimated by Covid spent six months on a business plan with my dad for getting into house building. Again, covid destroyed that whole business plan with you know, supply issues and materials. It was just crazy. But meantime I had been drafting these patents for various products and filing these patents and learning, being coached on licensing, which is where you have IP, intellectual property and there are various types of IP and you license out the rights for its use in return for a royalty, creating passive income. So the model itself, the way of the model working itself, was scalable. I could draft these innovations in a patent filing and get these royalties from these various sources. So that was the plan. So I had to give up the aviation idea, gave up the house building idea busy with two young children and just stuck to the products and just to kind of wrap up that story kind of briefly. Basically I realised I needed to focus on just one product and I realised how much I loved design for manufacturing DFM it's called in the industry, but basically the process of making your product manufacturable at scale. I absolutely loved that and designing the machine, the tool that can put a product together, and I love the idea of managing manufacturing. So I thought I'll just get on with manufacturing this toothbrush and after years of development with that it released just a few months ago, it's in the market, it works, and now I just need to make a business out of it, so there's lots of options within that as well. So lots of ideas there and opportunities, but that's the general story.

Dr. James, 7m 27s:

Wow, man, that's been cool, and can I share what I love about what you just said? You've just been willing to give so many things a go in terms of finding the right thing which aligns with your inner passion. Rather than just saying, actually, do you know what? I'm not necessarily that ignited by my career decisions that I made initially and you thought cheers to that. Rather than just accept that fate, so to speak, you just thought, right, actually I'm going to craft a better reality. I'm going to go out there and find out what else the world has to offer, because really there's an infinite amount of things, and I love how you just attacked that head on avant garde, bro. It's really cool.

Dr. Michael, 8m 6s:

Yeah, it was. There was actually a point where Bell had no choice but to do it because, within the practice, it was going to eat me alive. And actually, you know, I think I dodged a bullet with COVID because I don't I just don't think I would have had any emotional or mental reserves left to restructure the business around COVID. I think that might have finished me. You know, that's how, that's where it got to. But you know, when, when you're in those kind of desolate moments, you, you, you, there's an authentic voice that comes from within and there's an energy and and that's your passion, or passions. And when you scratch that itch, when you give it a go. You know, in 2012, 12 years ago, I started just writing a patent just for the sake of it. It's a tiny patent on this tiny little innovation, because I just had to do something that interested me, because running the practice wasn't doing it for me, and that ended up being granted. I got a full, granted patent from that. It was an amazing exercise, but my message is that scratch the itch. You know, if you have this passion, just feed it, water it every day. If it's 15 minutes, just give it that chance and the light from that will expand. There's a glowing light as direction to follow in life and you'd realize this is actually a fire burning inside me and you know it needs, it needs a, it needs that attention and nourishment, you know.

Dr. James, 9m 40s:

Well, do you know what and I don't want to make a forecast about me, but it's 100% about you but just to add to that, when I was in clinical dentistry, I actually quite enjoyed clinical dentistry. I gave it eight out of 10 and satisfaction, which is pretty good 8.2 to be precise, is what I gave it, because it wasn't quite a nine, but it wasn't enough. It was 8.2, which is pretty good, and that was enough for me to think, actually this is as good as it gets for a flipping career. That was enough to low me into complacency, effectively because, if it was four out of 10 or three out of nine. I'm going to take action here. I'm going to do something different. And it almost kept me in that zone indefinitely because I my belief at that time beliefs yourself are filling, and my belief at that time was this is as good as it gets, until a series of life events co-op meant that I couldn't actually be a dentist for a while and there was always other things that I really enjoyed as well surrounding dentistry, and it just meant I had more time to channel into that. And then I find other things that were literally 10 out of 10. And what I'm saying is that, in my opinion, my belief system is that there's that 10 out of 10 thing that excites absolutely everybody, but you can't actually find that thing unless you create space for it in your life and no one's going to come along and just say right, this is what you love, this is what you love, this is your passion. The accountability rests in each and every one of us to find what that thing is, Because half the time you don't even know what it is. How can you know what it is? A baby doesn't know what their passion is. A baby has no knowledge of the world. We're all an infant on different levels, expanding knowledge every day, and what I'm saying is that you have to go out there and find that yourself and you have to put that accountability as uncomfortable as that can be, you have to put that accountability in each and every one of us and own that. And yeah, I really believe there's that 10 out of 10 exciting thing for everybody. And it's song is like the product design thing. Yeah, what was that for you?

Dr. Michael, 11m 34s:

Yeah, and can I just add to that that for a love dentist who are feeling stuck that it can feel such an extreme move Because the first thought is right, do I need to forget everything about I've done in dentistry? Just dump the whole thing of spent 10 years being educated, five years of practicing? It just doesn't necessarily need to be like that, because the incredible thing about dentistry is it's such a vast and deep profession and its nature of its demands, which mean arranging the skills and awareness that it gives you the knowledge, the understanding, the understanding of the world and people and systems, technology face to face, you know, sort of prevent, a service to other people. There are so many angles that dentistry furnishes you and that makes sense that you're probably going to find an opportunity that suits your personality within dentistry. But not necessarily in practice, you know, not necessarily. The quintessential dental career is such a vast profession and industry there's going to be a niche for you most likely. Give it 10 years, say, you know, five years of education, at least five years in dentistry. You know, challenge yourself, get the exposure and just start to think personally. What is it? What are the elements within dentistry that are really kind of attracting. For me it was design engineering. So you know engineering with almost every dentist is a design engineer, but they just don't know it. Some people love that bit, some people just do it because they have to. But for me, the design of something that has to be engineered to function, to look good, to marry perfectly with a user interface, is essentially what conservative dental treatment does. You know, and you can extract that skill set, make use of the pun out of the industry and use it elsewhere. You know, in your passion, if that's your thing.

Dr. James, 13m 30s:

Love that man. Thank you for that and thank you for sharing what inspired you to go on this journey because really this stuff is in my opinion, anybody can do it, but it starts with taking action and it's a comfort, something. I look back on myself and, yeah, I didn't actually realise that a lot of things that were holding me back were just fear, talking like, oh, whatever doesn't work out in this and that and the other.

Dr. Michael, 13m 50s:

If you make your.

Dr. James, 13m 51s:

ROI it being successful every single time, well then, you're going to be disappointed. If you make your ROI I'm exploring when I'm learning then you'll always be happy, you'll always be an immediate benefit, whether it becomes widely successful and offers an alternative to dentistry, or whether everything stays the same. Man, we only have so much time to serve, anyway, anyway, anyway, anyway, let's talk about the product design. Sad to think, because this is something that people don't know. This is like a black box of information. Be with me, yeah, and I just have to explore and piece it together bit by bit, and I'm sure you spend a lot of time exploring to understand how the product design process worked, and what you really would have rather is that somebody just came along and said, michael, just do this, and it's only now that you can probably go back to that previous version of Michael and Michael and say Michael, you wasted your time, Just do this, this, this, this and this.

Dr. Michael, 14m 37s:

What were the biggest learnings about that? How does that process in fact? Let's start with this yeah, how does that process look like? How does it?

Dr. James, 14m 43s:

actually look the product design process.

Dr. Michael, 14m 44s:

Well, for me the process began when I was age three, apparently, and I was taking apart toys and looking at why on earth has it been made like this? Why? How does it go together? Why does it go together like that? How does it work? And since then I've been, you know, visually looking at an object and taking that part in my head and like, why, why did they put the button there? Right, it's not convenient to be there. They must have done that just because it makes it cheaper to manufacture and it bugs you and it's like right, and why is the tool shaped like this? Ah, it's because they've just made this assumption about the ergonomics. And so it literally comes from curiosity and an interest in the objects around us that we use to help to make our lives easier. And I realized when I'm using something like this has limitations, why, why? And I just always asked why about the design of everything around me. So that's really from you where the process began with the whole thing, and it's that interest and function of a product is meant to service, and I'm so passionate about when we design something, or it's a service or product, it must serve the customer completely, not necessarily perfectly, but it should be great for the customer User interface, absolutely love that. So that's where it began and before you know it, you've got a list of ideas, a list of solutions for everyday problems that people just take for granted they have to deal with. And that's actually what excites me and inspires me the most in maybe inspiring others that within everything around you there are assumptions built into and question what assumptions might be lying there, and that 10, 20 years ago, when that thing was designed, those assumptions might have changed, those factors might have changed a lot, like the Dyson air blade, right. So old hand dryers, right, when energy was cheaper or something you know. The energy was probably I'm guessing here but the energy was going into driving the heater element rather than the fan. But Dyson has made the energy be allocated more to the force of the fan to drive off the water, not to dry it, to drive it off your hand. So the assumption was about the energy costs, maybe. So he just challenged that assumption and saw the scope for innovation, you know, I mean, who would have thought you can reinvent the hair dryer? Who would have thought you can reinvent the toothbrush, my product, for example? I thought, am I being crazy here. Am I actually trying to reinvent the toothbrush? Why has this not ever been designed in the hundreds of years that we've been extracting teeth? So essentially and it's just to give you a specific example when a tooth is lost, you cannot actually clean the teeth next to the gap in space, because the angle that you need to get the toothbrush bristles in at is just impossible. The economics are impossible with current toothbrushes and the assumption the profession has made for hundreds of years is that, because space has now been created, we should be able to clean there. And that's why nobody's questioned the status quo of the toothbrush designs that are out there. And as I piece together this new architecture for toothbrush layout, I realized this is reinventing the toothbrush and it addresses the problem. And it was all built on this assumption that the profession was sitting with you know. So my message is for any aspiring developers or the creative types out there question the status quo. Why are we doing it like this? Really, really, why is it like this? And within that you might see an opportunity.

Dr. James, 18m 24s:

I love that man, so that was the process behind it, and then what? Does the actual process itself look like? Do you go to by the way, this is a company layman with zero knowledge of this topic speaking Do you go to the pattern office? Do you fill in a form? Is it online? Am I revealing my thinking to be that of a 19th century person by stating that that's my concept of how it works? I have literally no idea. I have no idea.

Dr. Michael, 18m 57s:

Yeah, it is such a vague field and it's just not really well published and people don't really know where to start with it. But essentially there's two parts to the technical bit the practical bit to making your prototype, basically, and the description of that verbally, and that then just gets connected to the patenting system. So, coming back to that, the technical bit is to physically define what your innovation is. Make up some prototypes with some modeling, clear or something. Get it 3D printed. You can hire somebody on Upwork to do a 3D sketch of your design and make up a 3D printed model. And if you don't want one single party to see the full innovation, you could get different parties to do a different bit, so with different components, and you can bring it together in secret at home. In the meantime, you're wanting to verbally, in words, define the innovation, define the aspects of it that make it innovative. Now, prior to that, you need to have searched through what is the prior art, which is the previous innovations that have been published or are available publicly. So they may not necessarily be published patents, but they might be in the public domain already, and it's easy to search on Google Patents and even Amazon. There's simple search for things, what's already in the market and what's already filed at the patent office, and it's differentiating your innovation to that prior art. That is the task here. Then, once you have laid out these bullet points, if you like, and done some drawings of your innovation because a drawing speaks a thousand words with regard in patent filings you can then file that document at the patent office for like $70. And it's now recorded. There is now a priority date to which you can claim in the future, back to as when you made that innovation. And once you've really got those pieces together and you're confident with that document it doesn't need to be 100%, but if you're kind of 99% confident with that document, that it accurately describes your innovation, file it. Then you can start talking to people. You can start talking to companies. You can approach them with a view to them taking it on under a license, for example. They could maybe buy it from you if they see the strength in it, if they like the innovation. And you can also approach a patent attorney to really turn it into a full blown, robust legal document. So my first patent I wrote 12 years ago. It was maybe like three or four pages, something like that, with lots of drawings and it maybe doubled in size with its development. Communicating with the patent office, they were incredibly helpful. It was the UK patent office, that one, the toothbrush one. By this point I had already filed three or four patents and my first version was like 10,000 words just for this toothbrush. I got the patent attorney on board when I was really happy with what I had written and then he added another 3,000 words, which was basically it was duplication, but in his terminology, just to remove doubt. So it's OK to duplicate things within that document. You'd rather be verbose rather than skimping on detail, because it's that detail that you've missed out. That could be the edge for somebody wanting to not infringe but basically steal your idea. They can have that edge of innovation upon what you've already worked on. So that's the basic process. So when you make that initial filing, which is so cheap £70, as I say, you've got a year. You have a year before you then need to escalate that to the next level of filing, which starts to need more time and a little bit more money. But within that year you can explore the commercial potential of that product. You can explore the manufacturability of it. Can this be designed for manufacture at scale, the whole business model, the feasibility of it and, within a year, if you've pitched it to various companies across the world. And there's no interest or you feel it's just not a gore, then you can leave it and it's really not cost you much. And this model allows you to have a few product ideas running at one time and see what sticks and learn about the process. It's a part time thing you can do alongside your dentistry. And also, just to add to this, there are other types of IP. So there's design, which is the visual innovation, how it looks something looks. So if you design a new cushion, that's design. And then there's the utility, which is the function, and essentially my innovation is to do with function. The other one is copyright, so I can do with song lyrics. So there's these various other. There is one other type of IP I've forgotten for now, but there's these four major types of IP that you can keep as an asset and gain royalties from.

Dr. James, 24m 29s:

Nice, that's some know-how right there. Okay, cool, so we've got the IP, we've got it patented. What's the next move? Because I'm honestly man, I'm fascinated by this. Like I said, this is like black magic to me. I don't know, the first thing about it.

Dr. Michael, 24m 42s:

What is the next?

Dr. James, 24m 43s:

move to actually get the product in your hand, or at least a prototype.

Dr. Michael, 24m 49s:

Yeah. So just to clarify, it's not patented yet, even though the process began four years ago. Right Now it's patent pending. But when it's as robust as what this is, you can get on with a full. You can build a whole company on that. Because when you've learned and, with your patent attorney, made it robust enough to that, the likelihood of it not being granted is so little that you can actually get on and build a company. And that's the case with 99% of the products out there. They don't. They don't just wait for the grant granting of a patent. It can take five, six years. You get on with it when you've got robust filing. That's covered every possible angle for somebody who might be trying to work around your innovation. So essentially you can actually build the business from day one. As soon as you've made that filing, just put that draft in, you can start a business in theory. So as you go through this path, it's a case of measuring risk and return and making advances when you get more proof that every aspect of the venture has become more and more probable to become successful. So, for example, once I've made the filing, I reached out to companies to measure their interest. I reached out to hygienists and therapists to get them on board, to give them their input with what they think. You know, if I didn't need to do this, but if somebody had said, look, I think you need to just tweak the angle of that aspect there, there's still time to go back in you could refile with that extra feature. So if you filed like two months ago and you've just it's just dawned on you or they say I wanted to do this a bit better and you design the redesign, one of the features, to make it do that better. If it does it better, you've added function and that new feature as a functional innovation that's probably worth putting into the patent filing. So for another 70 quid you could actually just go in and add that little feature. But you want to try and anticipate that obviously in the beginning so you can reach out to the market. You can reach out to the users, get their input just to refine the whole thing. Get proof of product market fit. So that's does this? Does the market want this product? So once you've got product market fit, then you can seriously start thinking about the business. Get your price points, start working out what it would cost to manufacture. If you can develop an interest in how things are manufactured. There are some good textbooks out there about design. What's it? Design manufacturing for design professionals? I think there's one called as massive textbook and it's just beautiful stuff in there about manufacturing all kinds of things. Just learn a bit about those manufacturing processes, what it takes to set up a production line within one of those processes, and you might be surprised at how affordable it is. I won't tell you what. I was quoted for the tooling for making this. But I found a local toolmaker, an artisan toolmaker, who made this for a fraction of the cost and suddenly it was just manufacturable at scale. You know I can now send this tool to China and slash my cost of goods by 70%. So I'm getting it produced just now in Glasgow and there is a margin there. There is a business with those production costs. It's not the margin I want to keep. I need to improve that margin if I want to really scale. But it gets me going. It gets the product into the market and just to add a bit more detail, if you're trying to test product market fit, you can have some prototypes made. I would urge people not to spend too much on prototypes. It's easy to get carried away when you see your innovation be born and as real as it's in your hands. You see it working and you've tested it and you just. It's easy to just fall in love with your innovation and have it on your mantopies and admire it every day. But don't get sucked down this grab a whole of expensive prototyping. Just prove that it works. Make it even just a 3D drawing on screen that you can colour and show people. You know they can look at it in 3D without you having to make a physical product. So I would urge people to do that and make a nice little pitch sheet. You know, make it appealing, make it look professional. Maybe think about a brand as well, so that actually that's the. LRIP branding. So, yeah, trademarks. So yeah, think about your brand and things like that the brand name might play into what it does, you know. So you can start thinking about that. I think I asked you along the way what you thought of my brand name a couple of years ago. But yeah, you can even ask people about that. You know they're not going to run away and steal and suddenly file to file your trademark, you know, steal your trademark. It's just there is this fear of somebody else stealing your idea. But you will learn how involved in complex and difficult, challenging, but amazing if you love it the product development process is that people are going to stumble at the first hurdle, usually if they even think about stealing your idea. So get on with it, follow this basic process and, you know, just move forward, be sensible, move forward. People are not going to steal it as quickly as you might fear, you know.

Dr. James, 30m 27s:

I think that's something that can potentially hold somebody back as well, because you need feedback to improve the product. You know the likelihood that you're going to be absolutely able to nail it with your own eyes and what's solely in your own brain is unbelievably slim, because it might be your version of good product. What does the market actually want? You need to ask other people. They are the market, they represent the market, so speak and then you're listening. You're actually spot on. Even with Dennis and Fest, there's so many layers to it that it's just it's going to. It would be really difficult to replicate, in my opinion. And with the same, exactly the same with product. There's so much to it. The barrier to entry on the knowledge front is so big that for somebody to just pinch it, it's just not feasible. It's really not feasible. And if you let that hold you back, if you let that unwillingness to share hold you back, then I actually feel it holds you back from creating your product as well, because you need that feedback when you're talking about it.

Dr. Michael, 31m 22s:

So that's a big limit of me, right there in that experience as well you know and that kind of yeah, and I just, I just want to add that you know, the security that you need within a venture probably most ventures comes from comes largely from simple forward motion. I realized that as I was going along this journey that simply by moving it forward each day, that was giving me the edge. For any possible people who want to steal the idea of when it eventually gets exposed in a public domain, the fact I'm making forward motion was adding security, because every forward motion adds as layer of complexity that makes an obstacle, that defines the obstacle that they would need to overcome. You know so and it's the, you know, the first move advantage. Obviously everybody knows about that. So, yeah, let's get on with it. You know, make the moves, just advance it forward, feed it, nourish it. You get security from that.

Dr. James, 32m 25s:

And have some fun as well, because this stuff is fun, you know and I always, you know, I always like to use the frame of the veteran when it comes to this stuff. You know, when you're 85, let's say you do it and nothing works out Right, when you're 85, are you genuinely going to regret trying it, trying it, or are you going to regret the fact that you never got around to it, and never? You don't have enough time because everybody has a clock that's ticking, but listen anyway, let's not get stuck on that rather whole too much. Everybody knows my thoughts and opinions and these sorts of things. The greatest, the greatest, the greatest thing that you can put yourself through is just to do it, because you learn so much in the action. It's incredible. Plus, as well as that, if you make a key metric fun, well, what it means is that you're actually enjoying the process too. So it's always got upside whether it works out to be this wild succession, but listen anyway enough about all of that. So I'm curious tell us apart the product itself. What actually is products Never got around to talking about?

Dr. Michael, 33m 21s:

it.

Dr. James, 33m 21s:

Yeah, I know that we've alluded that it's some form of toothbrush and it's interproctal between teeth.

Dr. Michael, 33m 27s:

Basically, when somebody loses a tooth, they newly exposed mesial and distal surfaces of the teeth adjacent to the dentulous space are at an angle that current tools cannot clean. And this toothbrush has the bristles at 90 degrees to everything else out there and you know. Okay, you can bend a TP brush into this shape, but that's not the correct use of a TP brush. You know TP TP is interdental. You know it needs supported by adjacent teeth. It doesn't work. For this. Hygienists and therapists across the globe are struggling to coach people to clean these areas and, again, because they can see it, they think people should be able to reach it, so they're advising. Single tufted brushes, which are almost like surgical instruments, are so fine. You cannot expect a 70 year old, 80 year old person to get that the distal of their upper seven is just not fair to expect to have the patient. And you can bend a TP brush, as I say, but it's not designed to be used on one side. It just, it just deforms again it doesn't hold its shape. So this toothbrush has a bilaterally supported double sided toothbrush head which allows you to apply quite significant force to the exact key area that you're trying to clean. It's got the bass technique built in. You don't even need to worry about that. It can work in anyone's hands. It's got a nice big thumb grip for the elderly if they struggle with dexterity, but it's for any age. As soon as you lose a tooth, 95% of you get 95% chance. You need this. I did a study in my own patients in my private practice. These are patients that have been attending for 40 years of this practice and across my 11 years in that practice I saw this pattern that we simply could not eradicate. I had patients crying in the chair because they're basically about to lose this tooth because of root carries and they simply cannot get their hand in their mind's eye. They cannot correctly position the toothbrush to get that angle or it's just physically impossible to get the toothbrush at the right angle. And seeing this, I thought enough is enough. We need to solve this and came up with this completely new architecture for toothbrush and it is basically a new category of toothbrush, you know. So, yeah, 75% of adults have lost a tooth and 95% of them cannot clean a plaque from all of these newly exposed mesolandestosurfaces. And it's funny because you see these adverts on TV, these models with full dentitions using electric toothbrush, and I'm just laughing. I'm like that's not 75% of people. Can we just address this elephant in the room here? 75% of them are losing their tooth and face this new problem. So the classic patient is partial denture wearer, filling that gap and exacerbating the problem. The embutment teeth are at massive risk when you're at partial denture. If we can clear that plaque every day, that's gonna solve the problem. Part of the dentures are great If we can clean the abutment teeth pre-implant, post-implant, even somebody that doesn't want to ever fill that space just keep that area clean with this. So that's the use. Cases are vast.

Dr. James, 36m 59s:

And just for the benefit of everybody who's listening on this podcast. Michael actually had the product and he held it up to the camera so we could see it in video, because we're on Zoom right now and to give everybody a description of what it is and tell me if I've done a good job with this, Michael. But this is what I could see. If you think of a toothbrush with rubber bristles, so they're a little bit more turgid and firm, imagine a conventional manual toothbrush Now take the head and spin the head around 90 degrees, so it's like perpendicular to the shaft and it's also extended a little bit from the brush.

Dr. Michael, 37m 38s:

Almost like a. It's like a flossette with a brush on the end a double sided brush on the end.

Dr. James, 37m 44s:

A flossette. I haven't seen one of those before Flossette.

Dr. Michael, 37m 47s:

It's like a you know when. It's like a double-armed thing that suspends floss at the end.

Dr. James, 37m 51s:

Oh, I didn't know they were called flossettes. But yeah, it's like that, except it's got a proper shaft that you can hold and as well as that, it's not just a little bit of it's not just a little bit of floss in between, it's actually got this proper robust head and these quite firm bristles. That's how I would describe it.

Dr. Michael, 38m 8s:

Anyway, michael Is that, what do you reckon? Yeah, you can check it out on the website ergoproxcom.

Dr. James, 38m 14s:

So Boom, even better, even better.

Dr. Michael, 38m 17s:

I'll take your says as far as the words, as you say.

Dr. James, 38m 18s:

And I remember, michael, when you were going through the design process. I remember we talked on the phone once and you were saying to me James, you wouldn't believe how much there is to get in the right stiffness of bristles. They have to be exactly this size, they have to be exactly this firmness, exactly this polymer for manufacturing process. But then they can't be. But then you want them to be this skinny, but they can't be too skinny because the molds don't go that skinny. I remember that.

Dr. Michael, 38m 43s:

Yeah, yeah, it's so involved, but you know, through dentistry, the elastomer, the amazing science of elastomers and the incredible properties that they have. I just knew that we could get the performance out of an elastomer bristle. And in fact, nylon bristles would actually be detrimental in this use case, because the structure of this brush applies the force so effectively that with nylon on a rigid base which nylon needs it would actually traumatize the tissues. So this base had to be flexible, it had to be stress breaker.

BY SUBMITTING MY EMAIL I CONSENT TO JOIN THE DENTISTS WHO INVEST EMAIL LIST. THIS LIST CAN BE LEFT AT ANY TIME.