Description

Check if your dental practice qualifies for capital allowances here >>> https://www.dentistswhoinvest.com/chris-lonergan

———————————————————————

UK Dentists: Collect your verifiable CPD for this episode here >>> https://courses.dentistswhoinvest.com/smart-money-members-club

———————————————————————

Does financial jargon leave you scratching your head? Yep, you’re not alone! In this episode, we chat with Peter Frampton, chartered accountant and founder of Wealthvox, who’s on a mission to make finances simple for dentists. Whether it’s income statements, balance sheets, or the difference between profit and cash flow, Peter breaks it all down in plain English so you can confidently take control of your practice’s finances.

We’ll also dive into practical tips, like how to spot red flags such as operating losses, and use Peter’s “RELAX” framework to assess your practice’s financial health. From juggling debt to figuring out where your money’s actually going, this episode is packed with insights to help you feel more in control.

Oh, and there’s a new Wealthvox initiative on the horizon to help dentists master their numbers. If you’re ready to ditch the confusion and make smarter financial decisions, don’t miss this one!

Don't miss out on updates!

Register here: https://wealthvox.com/dentists

Transcription

Dr James, 0s:

How I speak accountanese is a question that is pertinent and relevant to all of us dentists, given that we get our financial statements at the end of the year and we kind of have to describe what's going on. Or maybe we politely nod our head when our accountant is talking to us. But we definitely could know our stuff better, and that is exactly the theme of today's podcast, and I've got an expert accountant sat in front of me now. He does a lot of education whenever it comes to the general public and translating what those terms mean, and that's why I'm super excited we got mr Peter Frampton in front of us today. Peter, be lovely if we could have a little bit of an intro, because I know this is your first time in the podcast lovely to be here, James, great pleasure.

Peter, 36s:

yeah you, you've nailed there that I am an accountant. I'm a chartered accountant, qualified in australia, and uh, my big buzz is making it simple. And you know, I call myself a turncoat accountant because I'm here to tell people like your listeners that it's not them really, it's we accountants who make ourselves so difficult to understand. And actually it's also simple and that's what our business, wealthvox V-O-X, like, as in voice, we want to give voice to dentists so they can express themselves as well when it comes to their finances as they express themselves when it comes to, you know, fixing teeth.

Dr James, 1m 16s:

Yeah, absolutely, and I know that you told me before we jumped on the air that you've got quite an illustrious past of helping some pretty high-flying, high-profile people whenever it comes to this stuff. Wall Street was in the conversation as well, wasn't it?

Peter, 1m 29s:

Yep, look, we're an education company, right, and we teach all over the world, and what I'm most proud of is the fact that we work In fact, we work in secret, sometimes with senior executives who can't be seen to be learning this stuff, and we teach micro in Africa. So, from the top to bottom, we've got the top. We probably work with 30, 40% of the top 100 law firms in America. We work on the biggest names on Wall Street, we work with the banks in the city of London, and our job is to make it accessible, and that's why we're here today to really debunk the terms and explain it in terms that anybody can understand.

Dr James, 2m 11s:

Let's do just that. And you know what? I am definitely in the camp where I could know a lot more about the accountancy side of things a lot better myself, so I think I speak for most dentists whenever I say that to that too. So what we've done is we've actually went on to company's house and we've went and gone, got a statement of accounts, uh which is basically, in essence, a truncated, abbreviated version of what your accountant is going to send off to hmrc at the end of the year when they want to file your tax returns effectively. And this is the thing that confuses the heck out of everybody, because there's numbers and there's little descriptions of what they mean. So I've got this up on my screen right now. We're going to go through each term systematically. So what it means is you can go on to HMRC, onto Companies House, after this podcast and look at a statement of accounts and be able to understand what it means when you've listened to the entirety of the podcast. That's exactly what we're here to do today. Anything else you'd like to add to that?

Peter, 3m 13s:

Nope, that's exactly right. Particularly, yeah, we're going to focus on, as you said, financial statements comprise a whole lot of reports. Two of the most important reports that people have heard of are the income statement and the balance sheet. They're often referred to and then, you know, one of the things I'm going to talk about is how many different names for the same thing, for the same report that they have. That confuses people. It's like, how many names do you need? So the two, the two, uh, key statements that we'll talk about today in this example that you and I are looking at, James, is the statement of comprehensive income it's often known just as an income statement and then we're going to look at the statement of financial position, which is the balance sheet. So those are the two big ones that people have heard of, and I will explain exactly what they are telling us and why they're really quite simple to think about explain exactly what they are telling us and why.

Dr James, 4m 6s:

they're really quite simple to think about, and I'm glad you made that hyper clear, right? Because on this sheet in front of me, that's exactly how they're labeled. So when you go and look at your financial statements on Companies House, you'll be able to see those exact terms right there, just to remove any ambiguity. I love that.

Peter, 4m 19s:

Yeah.

Dr James, 4m 20s:

Okay. Well, on that note, let's proceed's proceed. Statement of comprehensive income for the year ended 31 december 2022. That's what this record says in front of me. Obviously, that's going to vary based on which returns you're looking at, but yeah, statement of comprehensive income for the year. Maybe if we could just start off with a little bit of a description as to what that is, and maybe if we could explain what is also known as its aliases are as well, because I'm sure there's different names for it, that's a good place to start absolutely so.

Peter, 4m 52s:

Uh, it's the key word in there is income, right, it's an income statement and, uh, comprehensive income means it's just a statement of all the income, because there are other situations where you have just some of the income and then sort of extraordinary sources of income are listed separately. So this is a statement of all the income, hence comprehensive income statement. So it's also called things like a P&L, standing for profit and loss, or maybe profit or loss, right, but often just called a P&L. So when your accountant is saying, oh, this is your P&L, they mean they're talking about your statement of comprehensive income and it could be also referred to as a statement of financial performance, right. So the key words here are performance or even, sometimes, activities. A statement of activities, right. And this report describes what you do. You as a dental practice do, or you as Microsoft or Apple do, you know? In other words, from top to bottom, it's the same. It's what you've been doing to generate value for the shareholders, which, in your case, is you right, for the owner of the company that you're talking about. So that's the key thing that the income statement is a statement. It's a description of what you do. And because it describes what you do, description of what you do. And because it describes what you do, it'll run over a period right From, let's say, the 1st of January through the 31st of December, when we get to talk about the balance sheet. That's different. Balance sheet's a snapshot, right Balance sheet's at a moment in time, midnight on December 31st, whereas an income statement tells you what you've been up to over that period. So it's a performance statement telling you how well, how and how well you've been generating value, right. So, again, this is all going to be about value. Now I could be talking. We're all obsessed with cash, right? So often we want to say, well, hang on, it's all about cash. Cash is one form of value, but there's other forms of value. When someone owes you money they haven't paid you yet, that's valuable, even though they haven't paid you yet, but you've got the right to be paid, and so on, right? So, just to recap, the statement of comprehensive income is a statement of performance and it describes what you've been doing, and there are essentially two I'm going to call them things for the moment that appear on the statement, and they are income and expenses, income and expenses, simple as that. But, James, here's where some of the confusion sets in. What is income, James, let me ask you. I don't want to put you on the spot, but because I know you'll give an answer that's typical of everybody, so it's quite useful for people here. You're not wrong if you just say well, hang on. Let me just listen to the words in the parts of the word income. What do you think income means?

Dr James, 7m 59s:

Well, to me it's the money that comes into your bank account.

Peter, 8m 2s:

Of course.

Dr James, 8m 3s:

It's your cash flow right.

Peter, 8m 4s:

Yeah, exactly. Well, it's not. But of course you'd think that and, as I said, one of the big themes today, James, is that it's not you and your colleagues' fault that we're so confusing. As I said, I'm here to betray my own profession and tell you how crazy we accountants are. Income does not come in, you'd think. Income comes in. And everybody thinks income is money coming in. It's not actually. It's actually income is a verb, not a noun. It's what you do that generates value. So, in other words, when you hear the sound of drilling at a dentist, that is income, because you're generating the right to be paid by the client and you know, say, you have four sessions and they're going to pay you at the end. You don't go home after the first session and think, oh, I didn't do anything today. Of course you did. You've generated 25%, a quarter of what they owe you, so you've generated value, right. And so it's not the money coming in, it's what you do in order to generate value, right? Look, I accept that for most dentists, as soon as you do the work, the money comes in. So we sort of start to think of them as one and the same. But they're not. The sound of income in a dental practice is someone in the seat, someone rinsing their mouth, someone you know having their teeth drilled and a mold made and a crown inserted and so on. Right, that's the work you're doing Now. Equally an expense is what consumes value. So if James give me an example of something breaking or wearing out or using up in a dental practice.

Dr James, 9m 47s:

Oh man, I'm going to say the chair. That's the obvious one. There we go or the suction that goes all the time.

Peter, 9m 52s:

There we go, so the suction breaks. Have you lost value? You had this beautiful working machine that's worth I don't know how many thousand pounds, and suddenly it's broken. Have you lost value?

Dr James, 10m 10s:

I'm going to say yes for two reasons, and it's one because you have to fix it and that's going to cost money, and then number two because it's opportunity cost that you would have otherwise had from the chair functioning.

Peter, 10m 17s:

I love that You're speaking like a wise practitioner there about the opportunity cost. I'm an accountant, so I'm not going to dwell on the opportunity cost. But you're quite right, there's an opportunity cost. But the main thing is that, from an accounting point of view, your chair was worth. Excuse me, I'm going to make up numbers which are probably way off. The suction machine was worth 4,000, 5,000 pounds and now it's broken, so it's worth 1,000 and you're going to have to spend more money to get it working again. So you've just lost £3,000 worth of value. You may get insurance and all those other practicalities kick in right, but the point is you can lose value left, right and centre, in other words. In fact, you're losing value all the time because just wear and tear and every time you use a Kleenex or a pair of rubber gloves and so on, that's you consuming value, all right. So, in other words, let's step back a second. We've got this report that tells you how well you're going at generating value. It's all about value. Income is what you do, that generates value. Expenses are what you do and what happens that consumes value. There's only two things happening in a dental practice at any time.

Dr James, 11m 26s:

from a financial point of view, as you know and just to just to jump on that for two seconds not just a dental practice, by extension, any business is that fair to say?

Peter, 11m 34s:

any business any business, whether it's apple, microsoft or a small dental practice, there are two things happening in your business uh, value generating activities happening and value sacrificing activities happening in your business. Value generating activities happening and value sacrificing activities happening. In other words, the traditional names are you're generating revenue and income. Revenue and income are synonymous terms, so again, it's one of those examples of lots of different words for the same thing Revenue, income is the activity of generating value. Expenses such as depreciation supplies, consumption of supplies those are the expenses, right, and this is one of the things that's so important that our work with dentists and you know, James, that we're planning this education in January, february, this workshop and what we really bring home to dentists is this mindset of value creation, value consumption. That's all that's happening in the business and that's all told on this statement of comprehensive income which covers the period. So it's really as simple as that.

Dr James, 12m 36s:

Okay, wow, well, I love it and I love those sorts of little distinctions, as in getting into the almost like academia of it, right, because I'm going to go out on a limb and say that even though that sounds like maybe a purely scientific or academic distinction, it actually has ramifications and other things that you do. Am I right in saying that? Absolutely they always do, they always do right and that's why always link up yep this. That's why it's so important to define it. So I love that and that's that's like a mindset flip, another way to think of yeah and what have you? and I'm sure, speaking on lots of dennis behalf, that they'd never heard that little distinction before, which is super valuable. Okay, cool, let's jump into the breakdown of what the terms mean on this statement of comprehensive income for the year. And one more thing just before we move on, one more thing that I like what you said. I love when people can just pull something out of the ethereal and make it really like binary, like it's either going to be this, this or a combination, and that's exactly what you did with the income and and expenses. And, yeah, when you. Yeah, we kind of know that stuff at a high level, but just to be able to look at this sheet through this lens, I think that's super useful as well. So let's go ahead and dive in. So am I right in saying we, in saying we've got this statement of comprehensive income for the year in front of me right now? Yes, we've got some terms here and I'll just read those off administrative, expensive, unrealized loss on revaluation of investment properties. This is for a property company. We're not going to disclose what property company, but it's for an investment company. Yes, then it says operating loss. Then it's. I'm literally just reading these off as you see the interest payable and similar charges lost for the financial year. So I'm gonna say that not every comprehensive, not every statement of comprehensive income has those specific terms on it. Am I right Exactly?

Peter, 14m 19s:

Because, as I said, there are just two things happening. Now, what's unusual about this statement of comprehensive income is they because they're a property company and they've kind of been dormant. They didn't have any income this year. So normally the first line and the income statement always works from the top down. The top line is going to be your revenue or income same thing, right Income and it might go into different types of income, right? So look, I've got and, of course, management accounts these are abbreviated accounts. So in your management accounts that your accountant will be preparing for you and your bookkeeping accounting system will capture, you'll break down different types of income, in other words, different types of value generation. So, James, name me three or four types of value generating activity that you do in a dental practice.

Dr James, 15m 13s:

Okay, well, I'm going to say the big one is going to be the treatment, and then virtually most things that generate value fall under that. So let's go fillings, let's go crowns, let's go skills and polishes, and then maybe we could say sundries as well, like little TP brushes and toothbrushes that they might sell at the front desk.

Peter, 15m 32s:

There we go, perfect, perfect. So those are all forms of income and that would be listed at the top of the income statement. You wouldn't report those to Companies House but for your own management purpose. You really want to track that. You really want to track that because it's useful to know. You know we're doing a lot of this type of work and it's not earning us that much profit. We're going to get to profit, which is at the very bottom of the income statement. So at the very top is income and at the very bottom is profit. And profit means the net value generated, because I've said, these first lines are what you've generated value. And we're then going to get onto expenses. And in the same way we divided up revenue, income by expense sorry, by types we're going to divide expenses up by types. And so let's move on. In this statement we're looking at in front of us, we've got administrative expenses right. That's again because the property company. But in a dental company you'd have direct what we call cost of sales. That's things you use up each time you're working on a patient. In other words, if you didn't work on a patient, you wouldn't have incurred that expense right, like amalgams and glues and braces and so on. When you use those up, that's a direct expense. So we go at the top of the income statement income, less direct expenses, amalgams, supplies and so on and then you work out the difference between those. If it's 100 and now you've used up 20, you've now got a subtotal that says 80 and that is called your gross profit 80. You've got a gross profit of 80, but we haven't taken into account all the other value sacrifices that we need. So what's a sacrifice that you make, James? That doesn't depend on patients coming or not. You're going to pay it anyway during the month.

Dr James, 17m 27s:

I'm going to say software costs.

Peter, 17m 30s:

Software costs, rent, it's like yes, or staff. Rent or staff, it's like yes, or staff, exactly. So you've got a dental hygienist there and you're paying him or her anyway, regardless of whether they're busy or not, let's assume, right? So those are what we call operating expenses. They're not sales-related expenses, they're operating expenses. So now you had your AT I'm making up just round numbers here and you take away your software costs, your rent and your basic salaries, and so let's say that's 50. We could be talking 50,000, 500,000, whatever it is. And so now you've got 80 minus 50 is 30, and that's your operating profit. So there you have it. You haven't taken away tax yet. So you see, you've got all these subtotals. You've got your gross profit. That only counts direct expenses. Then you've got all these subtopicals. You've got your gross profit that only counts direct expenses. Then you've got your operating profit that also takes into account operating expenses, operating consumption, and now we've got 30 as the profit before tax, for example. And you take away tax, let's say it's 10. So now you've got 30 minus 10 is 20, and that's your profit after tax. And what profit after tax means is how much net value are generated during the year. Now that value is going to show up in the form of assets, James. It's probably going to be a lot of cash, but not necessarily, because sometimes cash can go out and you'll look at the bank account and you'll say I've got no cash, I mustn't have made any profit. No, profit and cash are two different things. Profit is how much value I generated. Imagine if you took all your cash and you bought a new chair. So you took that whole 20,000 profit that we made right and you bought a new chair. So let's say you've got no money in the bank account. Now would it be fair to say you generated no value during the year? Of course not because you've got a whole new chair. It's just that you haven't managed and this is what we teach in our workshops how to manage the balance between where you put your cash, how much cash you need, how much it should be tied up in uh equipment and so on and so on so you're making the distinction between the costs that are necessary to perpetuate the business and profit that you've reinvested right. Profit is how much value you've generated. Reinvested is a funny term because it's like you almost took it out and put it back. It never left. You see that 20,000, remember in our little story we just told we had 20,000 profit. That's how much value we generated. Now, we never took it out. We had it as cash and then we bought a chair, and so it's never come out of the business. It's never gone to your pocket I beg your pardon, pocket. It's never gone to your pocket. It's never gone to your pocket. So when we get to the balance sheet, which we're going to do in a minute, you'll see how all the value you've generated is sitting there in the assets, and the assets are cash. Equipment could be deposits, it could all sorts of things. Profit can manifest in all sorts of ways.

Dr James, 20m 41s:

I understand, because technically okay, I'm a brain, I've just had like a eureka moment, right, because it makes sense, because cash is just one form of an asset. Thank you Say that again, say that again. Can't say it louder for the people at the back Cash is just one form of an asset. Cash is one, albeit critical, form of value. Exactly exactly there we go, which I, which does make sense, right like that, and I preach that all the time and it's like when one of the one of the principles of investing is that you want to store your money in an asset that's going to appreciate and value right, it's going to grow. Yes, now a fundamental, a fundamental property of cash. Cash is that there will inherently always be inflation, right like it's just how economies work right. Yes, we want to get it. It's probably like a 40 minute explainer as to why that's the case.

Peter, 21m 26s:

Maybe we'll do a podcast on it someday yeah, governments want there to be a little bit of inflation exactly. They want it to be two percent they want it to be two, two and a half percent.

Dr James, 21m 35s:

Yeah, exactly and it's necessary and we're not going to get into that. It's a conversation for another day, right? But the second you know that is also the second that you know that cash is not designed to be a long-term store of value, right? So you take it purchasing the stock, not financial advice. Purchasing the stock, right is just exchanging, that is, just turning that value. You transmute it into another form, another asset, and one of the characteristics, potentially, of stocks, if you get the right fund, is that they appreciate with time anyway.

Peter, 22m 2s:

Yes, I'm not going to get into that. I want to ask you a question here, James. What did you mean by stock?

Dr James, 22m 8s:

or did I hear you?

Peter, 22m 8s:

say stocks, and I'm going to. I'm going to tell you why I'm asking in a second oh sorry, what is a?

Dr James, 22m 12s:

What is a stock? Just to be clear, this is not the stock of a business. Stocks and shares. Stocks and shares.

Peter, 22m 18s:

Exactly so. Do you see what I did there? Everybody, all the listeners. Do you see what I did there? So James used a term. I knew what he meant. He knew what he meant. But I also know that those financial professionals is say stop, hold on, I'm not stupid. What did you just say? What is that? Because stock is another name for inventory. So when you turn around and you've got a drawer full of amalgam, that's also stock. That's why you do a stock take. And sorry, James, but that's just a lovely example of how the word sounds so similar but mean two different things. You're talking about investment stocks, stocks and bonds in the sense of shares in a public company, or example of a stock, correct?

Dr James, 23m 6s:

shares in a public company. Example of stocks. Yeah, absolutely, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah there we go.

Peter, 23m 11s:

Lovely it's. You know, James, there's a theme coming through here that what has people be intimidated by all this financial stuff is not the numbers. I mean. Your listeners followed when I said 80, well, I started with 100, didn't I? 100 minus 20 gave us 80, minus 50 gave us 30, minus 10 gave us 20. That isn't what stopped anybody. The confusion is actually about the words, and that's quite the revolutionary thing that my colleagues and I deal with is that we look at the language and when we get chartered accountants in the room and they say, oh my goodness, is that what people don't understand? Because all these years they've been using words not realizing what the other people hear when they say income and so on.

Dr James, 23m 52s:

There we go, there we go Different connotations for the same word. That's actually how lots of miscommunication happens. You say the same word, but somebody has a different concept of what that means. But we all presume we have the same shared concept, which is actually crazy when you think about it. Anyway, have we put drawn a really nice line under comprehensive income statement of comprehensive income?

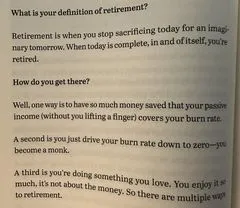

Peter, 24m 12s:

We have, so we work down to the bottom and then you have a profit or a loss at the bottom line, and that is for the period Now. Of course, if your expenses are greater than your income, if you've sacrificed more value than you've generated, then you have a loss. If your revenue is greater than your expenses, then you have a profit. So that's it, and the key thing is this report actually plugs into the next report we're going to discuss, which is the balance sheet or the statement of financial position.

Dr James, 24m 43s:

Absolutely. Let's jump straight in with that, shall we? So I guess a good place to begin is much like how we began with the last document or the last statement, and that was just to debunk some of the other terms that people use, some just, uh, not, maybe. Maybe not debunk is the right term just draw to attention some of the other use for this. Yeah, yes. Statement of financial position right?

Peter, 25m 5s:

so this is what's historically known as the balance sheet. Right, because there are two sides to it and I'll speak to what the two sides mean. So you've got the income statement is a statement of activities, of performance, it's like verbs, and the statement of financial position is the balance sheet or the statement of financial position, like. Take those words literally. This is where I am. The income statement we've just been speaking about is what I was doing, but this is the balance sheet, is where it's left me, right, and so it's always at a moment in time, at the end of the income statement. So, remember, our income statement went from January through 31st December. So this balance sheet is at midnight on December, the 31st, right, and there you have it. And then it's telling you what. You take this seriously. I'm going to say it slowly what you got and who you owe it to, where the you is your practice. Right, because the you isn't you, the you is your practice and you hope that the practice owes you a whole lot of money. The job of your dental practice LLC or incorporated or limited liability or proprietary, limited or whatever it is I'm not sure about how they're incorporated but the job of your practice as a business is to try and owe you as much as possible. That's what it's trying to do. It's trying to owe you and then sometimes it might pay you cash or it might keep the cash inside the business. But this speaks to the two things. There are only two things on a balance sheet what we call it the entity strictly speaking I've been talking about you, your business, but it's strictly speaking it's the entity, the accounting entity. So what the entity has, which is going to be things like property and I'm looking at the report we're sharing here, James this entity has property, investment property, it's got cash at the bank and those are its two assets. For a dental practice you'd have a whole lot of equipment. It might own the building, it might have some deposits, you know, like rental deposits in advance, all these valuable things. So anything that's valuable. There are some things we don't count like reputation, but anything that's valuable. There are some things we don't count like reputation, but anything that you've certainly, anything you've bought, that is going to show up as things the business has. And then the other side of this statement of financial position, the other side of the balance sheet, is who those things are promised to Right. So if the balance sheet has got a million dollars worth of assets, right, a million pounds worth of assets, right, to whom could those be promised? Just think of people who might sort of be saying, hey, hands up dibs, those are set aside for me. I've got my eye on those.

Dr James, 27m 58s:

I've got my eye on those. Well, let me see. So if you've got any creditors like, let's say, you've bought something on finance and you owe a certain amount back, then you're going to owe them the principal plus the interest on top right.

Peter, 28m 8s:

Absolutely. So you've bought supplies Did you say supplies or equipment or whatever? And you haven't paid them yet because you're on 60 days or you've leased it or something like that. So those are what we call creditors credo from the Latin trust. Right, they've trusted you, so you're calling them creditors, and yeah, so of those million dollars of assets, you owe them 300,000, let's just say, right, and yeah, so basically you've got $300,000000 worth of credits. Who else might you owe?

Dr James, 28m 41s:

Who else might you owe? Okay, let's think about this. Let's say that you have a leasehold, as in your dental practice. Well, the building that it's in it rents it from somebody else rather than you owning the building itself. So I guess you would owe them some money.

Peter, 28m 59s:

Well, you owe them a month's worth of rent or two, three months worth of rent, yes, so if you're, you see that's it depends. If you pay month to month, you're not going to owe them a lot because you're paying month to month. And it gets a little bit more nuanced where sometimes you might say one of your assets is the right to live there, operate there, for a year and one of your promises liabilities is the duty to pay them rent for a year. So that's a little bit slightly more advanced concept, not as clean cut. Let's just say you've got a bank overdraft, so you've got a bank overdraft. So we've talked about creditors. Creditors is people like suppliers or your leased equipment and so on. The bank overdraft they're also a creditor, if you will. Again, we use these words differently as accountants, but they're just a lender. Let's say so you have a liability, liabilities you see the word liabilities and creditors they both promises. They both promises to use that million of assets. You have the million of value to pay those people back. So let's make up some numbers here. We've said you've got a million of assets. We've said that you have creditors for 300,000 pounds and let's say you've got a bank overdraft for 600,000 pounds. I'm just making up some numbers here. So you've got a million of assets, you've got 300 creditors and you've got 600. You owe the bank. There we go. That's great. So who is the last person that the business owes, that it likes to owe?

Dr James, 30m 42s:

It's going to be the owner, the owner, exactly.

Peter, 30m 45s:

And that's what equity is. That's what equity is. People think equity is an asset. Well, it kind of is in your hands. But we're not talking about you. We're talking about your business, and your business wants to owe you. You know James's business business wants to owe you. You know James' business is trying to owe James more. James' business now owes him 100,000. Because we had a million minus 300, minus 600, that's minus 900. And so James' business currently owes him 100,000 pounds and next year it's going to see if it can increase that to 150, 200, 300, you know, 2 million pounds. Because that's what a business is trying to do. It's trying to grow how much it owes its owner and that's called profit, and profit is part of equity, isn't this exquisite James?

Dr James, 31m 33s:

I love this stuff right, Because you know, when you can just pull these terms out of the ethereal and define them as what we were saying earlier, then you all of a sudden see how they stack and they all interplay with each other. So am I right in saying I'm going out in a little bit of a limb here? But by extension of what you've just said, let's say, let's say in the bank account there's zero, Right? Yes? But let's say the business has loads of assets, right? So let's say the business has I don't know, we can just pull that out of the air Anything that holds value, right, yeah?

Peter, 32m 3s:

equipment. Paintings on the wall famous you've got a Picasso on the wall.

Dr James, 32m 8s:

Yeah, there we go right, exactly right. So actually that is the true definition of equity it's the total value of those assets less what the business owes its creditors. So they technically are yours in a way, even though you've got through. That is your equity in the business, even though you might have zero in the bank account at that given moment I love what you've said there.

Peter, 32m 31s:

I I could split hairs a little bit by saying you've got the assets of a million. Let's say you've got assets of a million and and then you owe the bank and credit is 900,000. So your equity is 100,000. Yep, it's just that there are two sides to the balance sheet and you immediately flip back to saying the leftover 100,000 assets, whereas I, through a sort of discipline, I want to keep saying equity is the promise to the shareholder. So it's not, it's not the, it's not the hundred thousand asset that's, that's unallocated, it's the promise. You see, this is the double entry of double entry accounting. That confuses people. There are two, two sides. You completely correctly said that the 100,000 is the amount of equity, but strictly speaking, equity is a promise. Have you ever seen a promise, James?

Dr James, 33m 26s:

Seen a promise?

Peter, 33m 27s:

No you've never seen a promise.

Dr James, 33m 29s:

It's a speech act.

Peter, 33m 31s:

If you've seen a promise, tell me how it looks. You might've seen a piece of paper that you know. Evidence is the promise, but a promise is just a speech act, just like a liability. It's a promise to the bank, your creditors, is a promise to the lease company that you're going to give it back, right, so you've got the assets, which are the things and the promises, back to the shareholders, the owners, the creditors of the bank, right, and it's these two sides and that's what we hold the professionals, the dentists, while they get there, really head around, this two-sidedness, and it's very empowering when you develop, you see, in the end, what we do is we build a model, and actually we do this in our workshops. You end up with a five-box model where you have the income statement we talked about first, and then you have the balance sheet and there are only five boxes. Everything that happens happens inside of five boxes, which we call RELAX, r-e-l-a-n-x, and that stands for revenue, equity and liabilities. Those are your promises, assets and expenses, right, relax. And when you get clear on relax, you can see in front of you what we call the value cycle and it's the full picture of your business, instead of being obsessed, as we all are, with cash in, cash out how much cash? You see the full operations of your business and it gives you such power to make better decisions I'll bet.

Dr James, 35m 0s:

I'll bet because you get a true picture of what's going on and how much money you have true and full picture yeah, I'll bet. No, I love that and I'm actually. I actually really enjoy stuff like this as well. So thank you for thank for enlightening this wall.

Peter, 35m 16s:

So if we go back to this statement of financial position, fixed assets and current assets are assets that are going to last for more than 12 months, so they fixed they're a long time. They're also called non-current assets. Right, keep going, James. I see you reading down the list here.

Dr James, 35m 33s:

No, I'm reading with my eyes, but I'm listening intently, so fixed asset fixed fixed assets are assets that are going to 12 months. What was that that you said Last exist?

Peter, 35m 45s:

expected to last for more than 12 months. In other words, they're not liquid. The reader of the financial statements knows that. Okay, those are going to be around in 12 months' time. And that is different to the next category, which is current assets. Right, or liquid assets that are probably going to be used up within 12 months. Stock inventory the amalgam that's in the drawers, your, your, your latex, gloves and things. Those are current assets. They're not going to be around in 12 months time right.

Dr James, 36m 15s:

And now? Now I can see my brain is forming some little connections here, because I can see that it is forming some little connections here, because I can see that it's like you've got the current assets. You're actually exchanging that value, right, because that's what they are for. More value, right? Yes, the patient gives you yes.

Peter, 36m 30s:

Why would you give valuable amalgam, valuable gloves, valuable wear and tear on your equipment? Why would you do that for a patient? Because they give you more than you give them.

Dr James, 36m 41s:

Is what's happening financially I I okay, that's an interesting way. I mean, this is the thing. It's kind of like we kind of know this, but I've just never really thought about it in those exact terms it's the exchange of value and there's a net gain there, absolutely absolutely well done.

Peter, 36m 59s:

I love that. It's beautiful for me to see you just this. The light's just going on, James piecing it all.

Dr James, 37m 5s:

I'm getting that. You know that. You know when you get like a little eureka moment and your brain is just like blah, like that, you know what I mean absolutely I've had a few of those in this podcast. Okay, creditors, amount falling due within one year. Is that exactly what we think it is, just from reading that bit of tax Exactly so.

Peter, 37m 20s:

That's like the promises that we talked about, but it's a promises that are falling due for payment within 12 months. So those are dangerous because you've got to settle those soon, Whereas a non-current liability is you know what. We're going to pay that back in five years. I'll get to that when I get you know, I'll worry about that when I get there, but it's tomorrow's payroll, it's tomorrow's overdraft, it's tomorrow's loan repayment falling due. That is dangerous and therefore I want to keep my eye on current liabilities.

Dr James, 37m 50s:

Right, I see, because, yes, you're using that terminology current right but you're just applying it to your liabilities now Precisely.

Peter, 37m 59s:

Precisely, Precisely. You have current and non-current assets and you have current and non-current liabilities. Yes, Understood.

Dr James, 38m 5s:

Okay, and then that obviously brings us on to the next one net current liability slash assets right, current being the operative word, right, exactly.

Peter, 38m 13s:

Current being the operative word. Exactly. So you've got net current liabilities, so that's those what's falling due soon, and that gives you in the end, like on this balance sheet we've got net, so in the end have you got more assets or have you got more liabilities? And here this company's got got more liabilities than it has assets. In other other words, it owes more than it has, and that's called negative equity. That's like when the mortgage on your house is 2 million but the house is only worth 1.5 million.

Dr James, 38m 48s:

Yes, understood. And when we get right down here, to the one at the very bottom here, so their net liabilities and assets, this is an interesting one and hopefully I can just read these numbers out without I'm sure I can. It's not too specific. Okay, I'll run the numbers. I'll run the numbers. It says, right here net current liability slash assets, and that's 3 million, 3 million negative and 3 million in brackets, right, which means 3 million negative, right? Yes, so that's what it says on net current liability slash assets. And then we get on to net liability and assets. As in no current, the word current is not there. This is overall Well, that's, that's more around the 40,000 mark. Net is the 40 000 that we talked about a second ago, but, focusing purely on 12 months, what we owe there's that they actually it's actually. Yeah, the net current liabilities is three million, but the net liabilities is 40 000, which is interesting, right? yeah yeah, yeah, have I interpreted that correctly?

Peter, 39m 53s:

you have this, this, uh, the. The difficulty this company has is that it has an investment property which is a long-term asset, but it's got debts against that asset in the short term. That's a dangerous position to be in because, look, they could turn around and sell the property tomorrow, right? But the key point is that the debts are falling due soon and the asset is a long-term asset. Look, eventually long-term assets get sold, but if it was under contract, they would have listed this property as a current asset, even though it's a building, right. So there's a mismatch between current and non-current here. They have potentially a liquidity crisis and, again, in the interest of time, we're about to wrap up, as you know, so we can't go into detail here, but that's what we learned to do Once we've learned to read these reports. Then we look at what to make of them and, therefore, what decisions we can make to improve things, sleep more peacefully at night, generate more value with less effort. That's the point of this literacy that we've started with today, James.

Dr James, 41m 9s:

You know what? And just on that, every single time I've bothered to learn how something works really well. I've literally never regretted it, because you can just see little things that you wouldn't be able to see otherwise. There's a little bit of a leap of faith, isn't there? Because it's so easy. It's such a human thing where we have that mindset where we're like hmm, but how much am I realistically going to learn? Right, and I think it's so easy to just go through life like that. But every single time I've had that little part of my brain say that to me and I've just not listened to it and pursued it anyway and bothered to inform myself. It's been worth it and this is exactly a good example of that, as far as I can see. Anyway, uh, as you say, we want to keep this podcast around the 40 50 ish minutes mark and I'm just conscious we're coming up to that as we speak. So let's go on to the last few headings on this document, and that is capital and reserves reserves.

Peter, 41m 59s:

So that's capital and reserves is another name for equity right. Capital is one of these most ambiguous terms. Remember I said relax, there's only five elements R-E-L-A-X revenue, equity liabilities, assets and expenses. Four of those terms sometimes are referred to as forms of capital debt capital, equity capital, a capital gain, a capital equipment. So you know again, it's we accountants are so confusing. Capital and reserves on this statement of financial position just means equity right and in other words, it's how much this business owes its owners.

Dr James, 42m 39s:

I see, and we've got called up share capital here for two million and we've got profits and loss, profit and loss account and that's uh, well, that's around the two million exactly 40,000 mark it.

Peter, 42m 54s:

Originally, the owners put in £2 million into this business. No-transcript negative equity this business owes people more money than it has assets with which to pay them.

Dr James, 43m 33s:

So you, if it stopped now, someone's gonna not get all their money back right, Okay, I get right, I understand, and that's why we have just below that, we have equity shareholder funds, right, and that's in brackets 40,000.

Peter, 43m 48s:

Exactly so actually if this business was to pay all its creditors back its lenders and creditors, creditors back it's lenders and creditors the shareholders would. They don't have to, but they would in theory, put a little bit of money in $40,000 into the business, not take money out to settle all of its debts. I see, when you sell the building you're not going to sell it for exactly the value that's showing on the balance sheet. In fact, the building might be worth a bunch more than is showing on the balance sheet. That's another longer conversation is where do these numbers come from? Like how do we know what a building's worth? If we paid two million pounds for the building 15 years ago, it sure as heck ain't worth two million pounds today well, chances are it's worth more.

Dr James, 44m 35s:

Right, because assets like that go up. We hope you have. You'd hope You'd hope. Yeah, not always. Absolutely. Okay, cool, well, listen, I want to say thanks.

Peter, 44m 46s:

Such a pleasure, such a pleasure, James.

Dr James, 44m 48s:

It's a brilliant podcast. I'm sure I speak on behalf of everybody to say that we learned loads and that demystified an absolute ton of this jargon, and you know what I can tell. And that demystified an absolute ton of this jargon, and you know what I can tell. I can tell two things about you, Peter. Not only do you know this stuff, but you teach this stuff right. Can you see the distinction I'm making? Simple's hard.

Peter, 45m 6s:

Simple's hard James.

Dr James, 45m 8s:

You see the distinction I'm making right, because you know the concepts, but you can also explain it and articulate it well, which I love. So thank you for that, Peter. Peter, you mentioned that you had a live day for dentists coming up.

Peter, 45m 19s:

Totally, we have we schedule it in in in, uh, february or march and we're going to be talking more with you about that. We're really excited about it'll be a two-day event, that that really it gets down to the nitty-gritty and it builds this foundation of literacy, the sort of stuff we've been talking about today. We have these hands-on boards where dentists are using it. This is the same we're using top law firms and investment banks. But because we address these foundations, we very quickly start talking about real value-added stuff, about how to make a dental practice much more valuable, how to then take those funds to invest them. We're not giving investment advice. We'll leave that to you guys. But when you're licensed, James but yeah, we're looking forward to it and sort of just I'm inviting your listeners to keep a lookout on your website or go to wealthvox.com forward slash dentists to find out more and just to register interest. We haven't opened registration yet, but we're taking registrations of interest at wealthox.com/dentists or your website, James, and really look forward to further conversations like this.

Dr James, 46m 30s:

Heck yeah, and I'm sure we can link that in the podcast description as well. So we will be comprised there super fast. Peter, thank you so much for your time, your wisdom, your knowledge. Looking forward to having you back on the podcast super soon.

BY SUBMITTING MY EMAIL I CONSENT TO JOIN THE DENTISTS WHO INVEST EMAIL LIST. THIS LIST CAN BE LEFT AT ANY TIME.